My heart is a flower, the corolla opens;

Ah! It is the mistress of midnight and She has arrived

Our Mother, the Goddess Tlazolteotl.

(Hymn to Tlazolteotl, from Baéz-Jorge 101)[1]

She is easily identified, usually with black around her mouth, sometimes with a conical hat or riding a broom, and often squatting in a birth-giving posture.

Tlazolteotl is one of the most endearing and complex goddesses of the Mesoamericans.

Her name is derived from the Nahuatl word for garbage, tlazolli, literally “old, dirty, deteriorated, worn-out thing … which was used to connote filfth, garbage, or refuse, all of which subsumed human waste products” (Klein 21). Tlazolli could also refer to profligate behavior, related to the root for quail (zolli), a bird associated with fertility and the earth “owing to its tendency to keep close to the ground and to its prolific breeding habits” (Sullivan 11). Indeed Tlazolteotl both provoked and pardoned licentiousness, explaining Her moniker “The Eater of Filth.”

The second part of Her name, teotl, signifies a deity, and in this generic form could refer to male or female. However, Tlazolteotl is almost always considered female. The early Spanish clerics compared Her to the Roman Venus because of Her connections to sexuality. Tlazoltetol not only encompasses illicit love, overindulgence, and dissolute behavior but also is the pardoner for those who engage in Her excesses.

Tlazolteotl is considered a lunar and agrarian Goddess. She is identified with the trecena [2] of the ritual calendar that begins with the day Ce Ollin, or First Movement. She is associated with the day sign of the jaguar. She was honored by the peoples of eastern coastal Mexico, the Huastecs, Mixtecs, and Olmecs, as well as the Aztecs of central Mexico. She was known by various names, including Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina and Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, indicative of Her many aspects.

Fertile and Generative Black

Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina originated in the rich fertile areas of the Huastec peoples in the lands bordering the Gulf of Mexico in the modern states of Hidalgo, Veracruz, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas. The Huastec region is a rich fertile area, especially known as a cotton growing region, with a long history of trading with Central Mexico. In a statue from post-Classic Huastec, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina wears a conical hat indigenous to this region.

On page 39 of the Codex Borgia [3], a ring of Cihuateteo (women who died in childbirth and were deified) dance around two figures. The Cihuateteo wear the typical red and black skirts and huipils of Tlazolteotl, adorned with crescent moons. The shells on their skirts, as well as the typical Huastec crescent moon nose ornament, connect them with the lunar cycles. Though the moon was considered the purview of a male deity, the cycles, the regenerative aspect, and the motion were female.

A number of Tlazolteotl figurines were part of an offering burial in honor of the Cihuateteo. These figurines show Tlazolteotl in Her aspect as midwife. In each hand She holds the bands used in traditional postpartum binding practice.[4] Though more obvious on these figurines in person than in photo, Her mouth is painted black.

In fact, Tlazolteotl’s most distinctive feature is the black on Her mouth and chin. The Olmecs used bitumen, a black viscous material, as paint for decoration on everything from pottery to the human body. Bitumen was chewed publicly only by girls and unmarried women (McCafferty 33)[5].

Bitumen (also called tar or asphalt) is the byproduct of decomposed organic materials. Could there possibly be a more apt decoration for Tlazolteotl than a paint made of deep, black, decomposed material associated with the burgeoning sexuality of young women? The black around Her mouth is linked with Her role as an “eater of sins,” as the “eater of filth,” but here the sin and filth are transformed into symbols of the dark erotic genesis of life.

Spinning, Weaving, and Sex

In her name Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, the Ixcuina is from the Huastec for “Goddess of Cotton” (Sullivan 12). Her headdress usually includes two spindles of unspun cotton, which connect Her to weaving and to the rich cotton-growing region of the Huastec.

In Mesoamerica, woven cotton textiles were used as a medium of exchange, and women were the principle weavers, bringing money and prestige to the household through their weaving. A spindle full of thread is also called a mazorca, the word for a full ear of corn, as they are similar in form. The strands of cotton that hang from the spindles in Her headdress mimic the tassel on the ear of corn. The life-cycle of corn parallels the cycle of spinning, from waxing to waning, and both parallel the human life cycle (Sullivan 28-29). Cotton had other connections to the female cycle, as the bark of the cotton plant was used for uterine contractions and to induce menstruation (Sullivan 19).

The act of weaving also had sexual connotations, as we see in this Nahuatl riddle: “What is it that they make pregnant, that they make big with child in the dancing place? The answer is ‘The spindles,’ and the dancing place is the bowl where the spindles are set” (Sullivan 14). Spinning and weaving were tied to women’s lives in metaphoric and concrete ways.[6]

Tlazoteotl-Ixcuina is associated with a four-part sisterhood: First Born, Younger Sister, Middle Sister, and Youngest Sister, each of which is named Tlazolteotl. This quadripartite representation may have lunar aspects, as the four phases of the moon (Baéz-Jorge 100). These sisters were the goddesses of carnality or lust, and the cleric Sahagún writes that “their names signified that all women have an aptitude for carnal acts” (36). I interpret this as an illustration of the female capacity, throughout her life, to embody the sacred cycle of generation, death, and regeneration. And certainly lust, the drive for connection and regeneration, is seated deeply in the female purview, and here most obviously connected to lunar cycles.

Purification and Pardoning

As Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, she is the “Eater of Excrement”, the pardoner of sins. Sahagún writes that the old or terminally ill would seek Her because this absolution could only be given once in a lifetime. Her clergy would not only hear confessions and grant absolution but would also find those, especially adulterers, who did not confess and bring them to public punishment. Tlazolteotl was invoked at a new birth, to cleanse a baby of her parents’ transgressions.

From the Tonalamatl de los Pochtecas comes a lovely image of Tlazolteotl. She is nude, wearing an elaborate headdress, and riding a broom. Her  headdress includes the usual spools of unspun cotton, as well as a shell, showing her ties with the lunar cycles. She is drawn with a wrinkled paunch, symbolic of a woman who has given birth. She holds a red snake, symbol of the fertility of menstrual flow (Baéz-Jorge 100) The broom is a reference to the Aztec purification festival of Ochpaniztli, which honored the female deities, including Tlazolteotl.

headdress includes the usual spools of unspun cotton, as well as a shell, showing her ties with the lunar cycles. She is drawn with a wrinkled paunch, symbolic of a woman who has given birth. She holds a red snake, symbol of the fertility of menstrual flow (Baéz-Jorge 100) The broom is a reference to the Aztec purification festival of Ochpaniztli, which honored the female deities, including Tlazolteotl.

As Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, She was the Goddess of the black, fertile earth, the rotting earth, the fecund earth that gains its energy from death, and in turn feeds life. Associated with purification, expiation, and regeneration, She turns all garbage, physical and meta-physical, into rich life.

Embodying the cycle

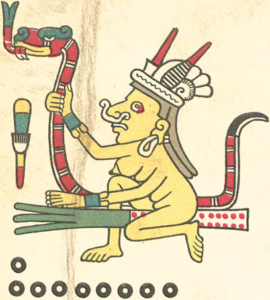

Tlazolteotl, Goddess of Cotton, Goddess of Filth, Eater of Excrement. She is the regenerative power of the earth, the midwife, and the pardoner. One of the most provocative renditions of Tlazolteotl is from the Codex Borbonicus (see image at top). She squats in the birth-giving position, wearing the conical Huastec hat with tassels, similar to the tassels on new corn. She wears black and red, decorated with crescent moons which, to my eye, mimic the shape of a vulva.

This drawing shows Tlazolteotl conceiving a child (see the child coming from above and to the right, footprints leading to the place of conception, the head), and She births a child who wears a headdress, earrings, and necklace just like her mother. While embodying this cycle of life, Tlazolteotl wears the flayed skin of the sacrificial victim (the dimpled skin always signifies this, but it is very obvious here with the extra hands hanging below), a symbol of death feeding life.

Tlazoteotl is associated with the trecena beginning with Ce Ollin, 1 Movement. The glyph for ollin shows the combining of two elements to form movement, symbolizing the active principle. The symbol for ollin is here as well in the two snakes to the right — one fleshed and the other discarnate. The two, intertwined, convey in vivid detail the interdependence of death and life.

In this image, She is the cycle of death and life, of death feeding life, of life cycling to death. The twinned snakes encapsulate ollin, the movement of life. Tlazolteotl is the provoker and the pardoner, the active female principle in the continual cycle of death and life.

Notes

- All translations from the Spanish are my own.

- A trecena is a 13-day period of time in the ritual calendar (the Tonálpohualli). The entire 260-day ritual calendar cycle consists of 20 “months” of 13 days each. The name trecena comes from trece, which is Spanish for thirteen.

- The Mesoamericans recorded their history and lore in a pictographic/logographic language drawn on long strips of paper referred to as “codices” (sing. codex). The paper, often made from deer hide, bark, or reeds, was whitewashed, allowing the full color of the graphics to be shown. The codices were often written on both sides of a long strip, and then folded accordion-style. The name of a codex often refers to its present location or owner. For example, the Codex Borgia was owned by Cardinal Borgia; it presently resides in the Vatican.

- “Massage and binding is a traditional postpartum ritual practiced by the Maya women in the Yucatan…. In the final stage of the massage process, another female relative (usually the mother-in-law) helps the midwife by laying the binder over the abdomen and passing the ends to each other under the small of her back. The binder is cinched around the pelvis as tightly as the woman can stand it.” Fuller, Nancy and Brigitte Jordan. “Maya Women and the End of the Birthing Period: Postpartum Massage-and-Binding in Yucatan, Mexico”. Medical Anthropology, 5(1): 35-50, 1981

- Bitumen was chewed by men only in private. Men publicly chewing bitumen were considered homosexuals.

- See McCafferty and McCafferty for a full examination of women and weaving.

Bibliography

- Báez-Jorge, F. (1988). Los oficios de las diosas [The stations of the goddesses]. Xalapa, Universidad Veracruzana.

- Fernandez, A. (1999). Dioses Prehispanicos de Mexico. Mexico City, Panorama Editorial.

- Klein, C. “Teocuitlatl, ‘Divine Excrement’: The Significance of ‘Holy Shit’ in Ancient Mexico. Art Journal, Vol. 52, No. 3, Scatological Art (Autumn, 1993), pp. 20-27.

- McCafferty, S.D. and G. G. McCafferty (1991). “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity in Post-Classic Mexico.” In Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, edited by M. Schevill, J.C. Berlo, and el. Dwyer, pp. 19-44. Garland, New York.

- Sahagún, B. (1999). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España [General history of things of New Spain] (A. M. Garibay K., Trans.). Mexico City, Editorial Porrúa. (Original work published 1829).

- Sullivan, T. “Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina: The Great Spinner and Weaver”. The Art and Iconography of late post-Classic Mexico, Ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. pp. 7-37.

Originally Published in Matrifocus.